Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

70 per cent of the world could be affected

Norwegian

researchers have calculated that 70 per cent of the world’s population will

experience a strong increase in peak temperatures or intense rainfall over the next

20 years, if greenhouse gas

emissions increase significantly.

Such a

drastic change in temperature and rain almost never happened in a

climate without human-made climate change, according to the new study conducted by CICERO, the Center for International Climate Research.

The changes in the next 20 years will be far beyond what has been normal and will be ‘unprecedented,’ according to the study.

At best, 1.5 billion

people will be affected

Tropical

and subtropical areas are expected to experience the most significant changes.

If the

world manages to achieve the two-degree target from the Paris Agreement, the

proportion experiencing ‘unprecedented changes’ will drop to 20 per cent of the world’s population. However, this still includes countries like India and those on the Arabian Peninsula.

“In the best-case scenario, these rapid changes will affect 1.5 billion people by 2040. In the worst case, we’re talking about around 5.5 billion people,” climate researcher Bjørn H. Samset says in an article from CICERO (link in Norwegian).

“The

only way to deal with this is to prepare for a situation with a much higher

likelihood of unprecedented extreme events, already in the next one to two decades,” he says.

Even if we follow the two-degree scenario, we still need to be prepared for rapid changes and

adapt to them, says CICERO researcher Carley Iles, who led the study.

How rapidly will things

change?

In the study, researchers relied on numerous simulations using climate models.

They did not run the climate models themselves but downloaded the results.

The

researchers focused on the five consecutive days of the year with the most

rainfall and the day of the year with the highest temperature.

They examined how much the maximum temperature has increased per decade and whether it has rained more or less on the days with the most rainfall.

They

compared the years 2021 to 2040 with pre-industrial times, from 1850 to 1900.

The

researchers looked at whether future changes will surpass the natural

variations of the past.

“Even in a

climate without human-made climate change, there would have been some variation,” says

Iles.

However, researchers observed that in many regions, the temperature on the hottest days is projected to rise by about 0.5 degrees per decade. Previously, the most common change was close to 0 degrees.

For maximum rainfall over five days, the pattern varied more across different regions. Yet in most areas, the amount of rainfall increased more per decade than what was previously normal.

Carley Iles led a study on how quickly the weather has changed in the past compared to what we can expect in the coming decades.

(Photo: Elise Kjørstad)

Unusually rapid changes in extreme weather

The

researchers have found that most of the world, including Norway, will

experience a rate of change in extreme weather that they describe as ‘unusual.’

This

applies to both the worst and best future scenarios.

This means

that such changes over two decades could have occasionally occurred in

pre-industrial times, but they would have been rare.

Convoy driving on Norwegian National Road 7 near Nesbyen, Norway in August 2023 after heavy rainfall caused the Hallingdal River to overflow its banks.

(Photo: Stian Lysberg Solum / NTB)

But is it

really that dangerous if the hottest day of the year gets a little warmer? It’s just one

day, after all.

Unusual changes

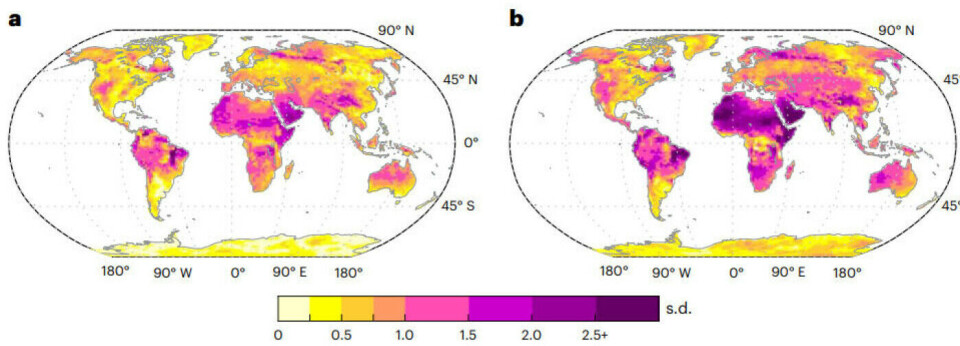

The researchers differentiate between changes that were 1 or 2 standard deviations outside of what was considered normal in the past.

Change is defined as the increase in degrees Celsius per decade (for the hottest day of the year) and the change in millimetres of rain per decade (for the five wettest days of the year).

- For the combination of rain and temperature, 2 standard deviations mean that the average change over the next 20 years falls outside 86.5 per cent of the results for 20-year periods in pre-industrial times. The researchers describe this as an ‘unprecedented change.’

- 1 standard deviation falls outside 40 per cent of pre-industrial values, which the researchers refer to as an ‘unusual change.’

- For rain and temperature separately, 2 standard deviations fell outside 95 per cent of values, and 1 standard deviation outside 68 per cent. It was easier to exceed these thresholds when looking at rain and temperature combined.

“While we

focus on the hottest day of the year in our study, other research has shown

that heatwaves, in general, are becoming warmer and more frequent. We expect

that annual and seasonal average temperatures will also rise,” says Iles.

“So I

expect we would find the same results if we used a broader definition of heatwaves, encompassing several consecutive days,” she adds.

The figure shows the average change for the next 20 years for both maximum temperature and rainfall. The colours from yellow to purple indicate how far from normal the results are compared to pre-industrial times (purple represents the biggest difference). Figure a shows the two-degree scenario (SSP1–2.6), while figure b shows a worst-case scenario for greenhouse gas emissions (SSP5–8.5).

(Image: Iles et al., 2024)

Particularly rapid changes in warmer regions

The

researchers also looked at maximum temperature and rainfall separately.

“Almost the

entire world will experience unusually rapid changes in temperature extremes,

but in some regions, the changes will be especially fast,” Iles says.

“In terms

of temperature, parts of Africa, the Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula and

parts of South America will experience the greatest changes,” she

says.

As for rainfall, there was only one area where the change exceeded the threshold to be

called ‘unprecedented,’ and that was in central Africa under the worst

climate scenario.

“In regions with ‘unusually rapid change,’ high-latitude areas, East and South Asia, and central Africa stood out,” she says.

Norway will

also experience unusual changes in rainfall in the worst-case scenario.

Due to the way the calculations were done, it was easier to exceed the two thresholds for combined rainfall and temperature than for each individually, Iles explains.

Interesting study, but rough description

The increase in global warming raises the likelihood of more frequent and intense rainfall events, partly because warmer air can hold more moisture, according to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (link in Norwegian).

Research

from the institute also suggests that climate change will cause rainfall to cluster over smaller areas, making it more intense.

Rasmus

Benestad, a climate researcher at the Meteorological Institute, finds the

study interesting.

He points out that global

climate models have limitations when it comes to extreme weather because they

are designed to recreate broad patterns, not local conditions like extreme rainfall in small areas.

Because of

this, international research groups have developed a program called

the Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX).

In this program, results from global climate models are processed by adding information about

local conditions and how they interact with larger-scale changes. This process is known as downscaling.

“The global

climate models only offer a rough description of, for example, mountains and landscapes, resulting in an image with coarse pixels. They don’t provide

good enough detail to assess the consequences of changes for the

environment and society,” says Benestad.

He also emphasises the importance of evaluating the models being used, to ensure

they can accurately reproduce the conditions necessary for studying historical trends in

maximum annual temperature and extremely wet five-day events.

“There are

many studies that don’t place much emphasis on evaluation, but this study does to some extent. I would say the results paint a credible picture, but should still be taken with a grain of salt – something that is also acknowledged in the article,” he says.

Flatten out

The

researchers behind the new study also looked at what happens after 2040.

In the low-emissions scenario, the increase in maximum temperature and rainfall intensity

begins to level off and stabilise by 2100. Temperature and rainfall will then

remain at a higher level than before.

The

extremes, on the other hand, continue to rise in the high-emissions

scenario.

The researchers point out that climate change will affect a large part of the world’s population, even with significant emission reductions.

Reference:

Iles et al. Strong regional trends in extreme

weather over the next two decades under high- and low-emissions pathways, Nature Geoscience, vol. 17, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01511-4

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.