Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

Can the new Hockey India League replicate IPL’s success?

“I feel proud because hockey ne rasta dikhaya (hockey showed the way),” Tirkey told Mint in a telephonic interview. The PHL sowed the seeds of India’s transformation into a nation of franchise-based sporting leagues, such as the near-$16 billion Indian Premier League (IPL), which launched three years later in 2008.

In the four editions of the PHL (2005-2008), Tirkey twice led his teams to the title–the Hyderabad Sultans in 2005 and the Odisha Steelers in 2007. Later, in the first incarnation of the Hockey India League (HIL), he was a mentor of the Kalinga Lancers. In 2017, he would again exit the HIL as a champion, albeit from the dugout. Now, as the president of Hockey India, the governing body for hockey in India, Tirkey faces a new test: the revival of HIL.

Last Friday, the league took a big step forward with the announcement of the franchise owners for the men’s and women’s editions. In the men’s competition, the teams will represent Chennai (owner: Charles Group), Lucknow (Yadu Sports/JK Cements), Delhi (SG Sports and Entertainment), Kolkata (Shrachi Sports), Odisha (Vedanta Group), Hyderabad (Resolute Sports), Ranchi (Navoyam Sports Ventures), and Punjab (JSW Sports).

Four of these owners, including Shrachi Sports (Kolkata) and SG Sports and Entertainment (Delhi), have taken up teams in the women’s competition. JSW Sports will own the Haryana women’s franchise, whereas Navoyam Sports Ventures will take up the Odisha franchise.

In a way, the new league could not have been timed better. The Indian men’s hockey team’s back-to-back bronze medal finishes in the Tokyo and Paris Olympics have provided the national sport with the necessary tailwind for a league. Such momentum can help it win a significant percentage of the nearly $250 million that India’s non-cricket sports command in terms of spending, as per a 2024 sponsorship report by GroupM. Numbers aside, the underlying opportunity is the emotional cachet the sport continues to enjoy with fans nationwide, evoking a sense of national pride.

View Full Image

A file photo of Dilip Tirkey.

There’s also a pragmatic case for the sport. Barring cricket, hockey is the only team sport where India stands a “realistic chance of being world champions in the foreseeable future”, to borrow from Ravneet Gill, co-founder of Big Bang Media Ventures, the commercial rights and marketing partners of Hockey India. But, given its checkered past with leagues (the PHL and the first HIL, which shut down in 2017), hockey’s third take can ill afford to get it wrong. That means throwing away past playbooks while adapting the sport to the demands of 2024 by making it relevant and relatable for younger audiences.

Ahead of its time

Anurag Dahiya beams from ear to ear as he starts talking about his “baby” over a Microsoft Teams call from Dubai. Dahiya, the current chief commercial officer of the International Cricket Council (ICC), was the brains behind the PHL during his stint at ESPN-Star Sports in the early 2000s. Predictably, cricket was the network’s biggest driver, and as a company, Dahiya and Co. scouted for alternatives with only one objective: building a world-class product.

And so came hockey, a sport that was enjoying a bit of renaissance at the turn of the century, courtesy the men’s national team’s achievements: the 1998 Asian Games gold (Kuala Lumpur), a near miss (for the semifinal slot) in the 2000 Sydney Olympics, 2002 Asian Games silver (Busan), and a famous win over Pakistan in the 2003 Asia Cup. Additionally, a new generation of hockey stars had emerged following India’s junior hockey World Cup win in 2001.

View Full Image

A file photo of Anurag Dahiya.

ESPN-Star Sports took a long-term view, first by taking minority ownership (with Leisure Sports Management) in a company, which gave it “entrenched ownership in the second-rung sport in India”, and then shelling out $4.25 million for the league’s media rights (for ten years). It had the backing of the then-governing body, the Indian Hockey Federation.

That meant that ESPN-Star Sports could start with a blank slate, take a relook at the sport, and reorganize it. “People didn’t have brands in sports that they could own and rally behind because they didn’t grow up with that,” says Dahiya. And thus, city-based teams such as the Maratha Warriors, the Hyderabad Sultans, and the Chennai Veerans were born.

It also had to look good on television (first) and make money (later). Enter a move that would transform hockey as we know it today: splitting a hockey match into four quarters of 17.5 minutes each. The sport, back then, was divided into two halves of 35 minutes each.

The rationale was to speed up an already fast-paced game besides providing advertisers with extra inventories. Even the points system was heavily incentivised (eg: three points for a regular time win and two points for an extra time win).

“The idea was to make players really go hard during that game itself and also try and keep a broadcast slot so that you aren’t overrunning too much,” Dahiya recalls. Joy Bhattacharjya, Dahiya’s then-colleague and now CEO of the Prime Volleyball League, adds, “Even the jerseys, the colours, were chosen with broadcast in mind.”

Just as the league was taking off and cementing itself in popular culture, it all came crashing down, courtesy an alleged corruption scandal in 2008 involving Indian Hockey Federation secretary Kandaswamy Jothikumaran. The PHL never recovered, with jittery sponsors distancing themselves from the tainted federation.

But even then, PHL is billed as a success story, with immense recall value. “Whenever I am on flights or airports, people stop me and say you captained Maratha Warriors. It was launched in 2004, and we’re in 2024,” says Viren Rasquinha, a former India international.

View Full Image

A file photo of Viren Rasquinha.

The big refresh

It’s been seven long years since India had a hockey league. In 2013, when the HIL first began, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg was just a year into his acquisition of Instagram. A decade later, that app counts nearly 363 million Indians as its users, per Statista. It’s a delta that hockey might want to tap. The main challenge for a league is to retain viewers (and attract new ones) year after year, something the IPL has done very well. Hockey India, under Tirkey, has made this one of its priorities.

“Hockey is one of the world’s fastest sports, and in one of the world’s fastest sports, we’re one of the best,” says Gill, formerly the MD and CEO of Deutsche Bank India, referring to one of the three boxes that must be ticked. The other two involve creating cult figures, learning from cricket, and then, integrating the sport with social media and the creator universe, making the sport relevant for the reels generation.

View Full Image

A file photo of Ravneet Gill.

“During our conversations with Hockey India, we insisted on ticking these three boxes, and I have to say that the governing body has been exceedingly supportive and proactive in this respect,” he adds.

That also needs a good chunk of marketing moolah. Industry estimates peg the Indian Premier League, alone spending around ₹40 crore to market the tournament. Industry insiders told Mint that Hockey India could set aside ₹25 crore every season to promote the league, a substantial departure from HIL 1.0, when the broadcaster mainly shouldered the expense. A healthy marketing budget is a good starting point, but it hardly guarantees success. For that, Gill has a non-negotiable checklist.

First, a world-class gameplay, i.e. where the world’s best players end up participating. HIL is expecting over 1,500 registrations from the top 15 hockey-playing countries, courtesy of a scheduling window. Scheduling was among the key issues that led to the HIL’s demise in 2017. A window also allows hockey (and its stakeholders) to build with predictability. “India is a country of ‘festival viewers’ when it comes to consuming sport. It needs a bandwagon effect. Hockey will have to own that season,” says Bhattacharjya.

Second, the quality of the franchise owners had to meet critical parameters: strong financial standing, sound reputation, and prior experience in having promoted sports. Not only would this guarantee a degree of commitment but also add to the attractiveness of the league with sponsors and broadcasters. This is where the league has emerged wiser from its previous avatar, where two franchise owners pulled out after its first edition.

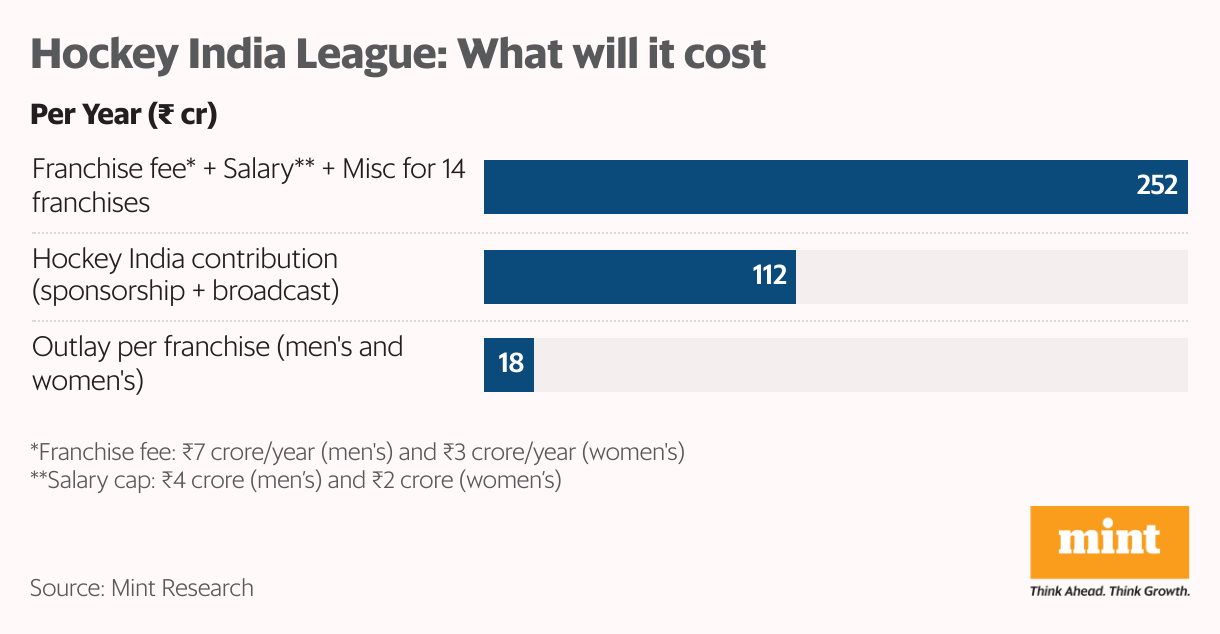

Lastly, there has to be a financial structure around the franchise fee that eventually establishes a path to profitability. The last point is a key concern for sporting franchises, considering that they typically bleed money for the first six to eight years. After all, a flawed business model, among other reasons, played a big role in the shuttering of the previous incarnation. The franchises, according to media reports from 2018, were incurring losses to the tune of ₹10 crore every season and were reluctant to participate further.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation for the current league pegs a franchise owner losing anywhere between ₹15-16 crore (lower end) and ₹17-18 crore (higher end) in the first edition— ₹11 crore of which could include the franchise and player fees alone. The other ₹4 to ₹7 crore could include costs such as jerseys, camps, and other outlay such as marketing and GST, according to a leading sports marketing agency.

The teams are expected to earn money from sponsorships and will be entitled to a share of the central revenue pool, much like the IPL.

In an effort to keep costs low, at least in the first year, the league has opted for a two-venue model in Rourkela and Ranchi, 3.5 hours apart by road. “The economic model should not be complex for a league starting up,” a sports marketing executive tells Mint, on condition of anonymity. But, to prosper, it must overcome teething problems and survive.

One proposal to this end is to have a “coordination council” with equal representation for franchise owners and Hockey India. “The decision, let’s say, for a player auction or a draft. Best that the franchise owners and Hockey India decide that collectively … as opposed to being decided unilaterally,” says Gill.

Nurturing talent

Hockey also needs a strong domestic league. The current structure involves an elite camp for national players in Bengaluru and a few senior national tournaments. “A strong league is one of the parameters of building a strong sport. And given that hockey is our national sport, and its importance to the country, having a strong two-month league is very important,” says Rasquinha.

It pays off when a league does its core job—bolstering the talent supply for the national setup, as HIL 1.0 did, providing India with its bronze-winning Olympians. “I remember the core of the Indian team actually started during HIL. Manpreet, Mandeep, Sreejesh, Amit Rohidas—they all made their name playing in that league and got rewarded,” Rasquinha adds. “Ditto with Sumit, who played in the Tokyo team. Before HIL, no one had heard about him.”

The biggest leap HI is taking this time around is in debuting a women’s league. While the Indian women’s team didn’t qualify for the Olympics, it is a consistent top-12 side.

Build first, monetize later

The legacy of the PHL’s model was its attempt at trickling the sport down to fans. But to engage them further, Dahiya says, they need to try the sport at least once. “A grassroots initiative, whether it is with schools, with softball, or five-a-side games in basketball courts, is a must. Kids need to experiment with it. Because, when you see the sport on TV, you have to know it is very hard,” says Dahiya of the ICC. “That’s when you appreciate it a lot better.”

But to get there, it needs a good, solid product for hockey fans. “The focus should be on building a great product that resonates with hockey fans. Monetization, in any shape or form, should only be considered after you’ve achieved some success in this,” says Yannick Colaco, co-founder of FanCode, a sports streaming service.

This is the challenge that awaits Tirkey. “We need a long-term vision from the franchises,” he told Mint, adding, “Without their support, we can’t grow the sport.” But given his Midas touch, Tirkey might well pull off another league win. His biggest yet.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.