Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

The economic gap between Africa and the rest of the world is growing – Cocorioko

The Economist Magazine

25 January 2025

The economic gap between Africa and the rest of the world is growing …

Business as usual will not narrow it, says John McDermott

In many ways, there has never been a better time to be born African. Since 1960, average life expectancy has risen by more than half, from 41 years to 64. The share of children dying before their fifth birthday has fallen by three-quarters. The proportion of young Africans attending university has risen nine-fold since 1970. African culture is being recognised worldwide; in the 2020s African authors have won the Booker prize, the Prix Goncourt and the Nobel prize for literature. This year the g20 will hold its first summit on the continent, in South Africa. All of this progress augurs well for the world’s youngest and liveliest continent.

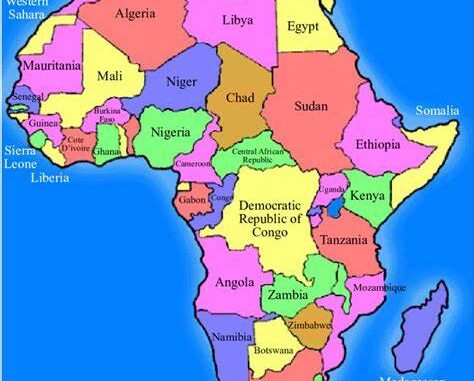

And not since prehistory has there been a time when people were more likely to be born African. The total population of its 54 countries has doubled in 30 years, to 1.5bn. The un predicts it will double again by 2070. Most of the population growth expected over the rest of the 21st century is expected to take place in Africa. These new generations are already leaving their mark. Political parties that trace their roots to the independence struggles of the 20th century are losing support from a generation of better educated and digitally connected Africans. In the past decade nearly 30 incumbents have lost general elections.

Demography, urbanisation, politics and consumer technologies mean the continent is undergoing profound social change. But that change is not being supported by economic transformation. Instead, African economies are falling ever further behind the rest of the world. In 1960 gdp per person in Africa, adjusted for the different costs of goods in different places (so-called purchasing-power parity, or ppp), was about half of the average in the rest of the world. Today it is about a quarter. Then the region was roughly on a par with East Asia. Today East Asians have average incomes seven times higher than those in sub-Saharan Africa. When plotted (see chart) the steadily growing gap looks “like the jaws of a yawning crocodile”, says Jakkie Cilliers of the Institute for Security Studies, a South African think-tank. One line rises up, the other stays almost flat.

In terms of the great issues of the 21st century, the fact that Africans are becoming relatively poorer even as they are powering the world’s population growth ranks up there with climate change and the risk of nuclear war. On current trends Africans will make up over 80% of the world’s poor by 2030, up from 14% in 1990.

Real changes, lost chances

Though the continent seemed to have made a promising start to the 21st century—this newspaper went from lamenting the Hopeless Continent on its cover in 2000 to celebrating Africa Rising in 2011—the growth spurt was short-lived and comparatively weak. Even in the heady days of 2000-14, when real gdp per person rose by 2.4% per year, other developing regions were growing more than twice as fast and creating more jobs. Since then, despite some stellar performers, income per person has stayed flat. The World Bank talks of “a decade of futility in economic performance” in sub-Saharan Africa.

By 2030 Africans will make up over 80% of the world’s poor

This feeds a growing concern that Africa may have missed its moment. In the 2000s African economies were buoyed by Chinese demand for commodities and by the rise of globalisation. Widespread debt forgiveness, finalised in the mid-2000s, meant that African governments could spend more on schools and infrastructure and take on new loans more easily.

It is wrong to say that the opportunities afforded the continent at that time were all wasted. Abebe Selassie, the head of the imf’s African department, likes to remind those stressing about the latest crises in Africa that, although these may be tough times, the continent is in much better shape than when he was a young Ethiopian technocrat in the early 1990s. “If anybody had said to me then that Accra, Kampala and Addis would, 30 years on, look anything like what they do today, I would have thought they were under the influence of more than just a cup of strong Ethiopian coffee,” he said in a speech in July.

And the region can boast some enduring success stories. Over the past 60 years Botswana, Mauritius and the Seychelles have grown at a clip, roughly keeping pace with the rise in gdp per person elsewhere in the world. More recently countries such as Ivory Coast, Ethiopia and Rwanda have chalked up impressive growth. But they have been exceptions rather than the rule. And the largest economies—Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa—have been especially sluggish. Even before the twin shocks of covid-19 and war in Ukraine, some were asking, in the words of the title of a paper co-authored in 2019 by Indermit Gill, now chief economist of the World Bank: “Has Africa missed the bus?”

In most of Africa most people are poor and productivity growth remains sluggish. As long as that continues the continent’s youthful population will not be able to become the force for change that it ought to be. “We have to create jobs for our young people,” says Mavis Owusu-Gyamfi, president of the African Centre for Economic Transformation, a pan-African policy institute. “They can’t keep being labelled an ‘opportunity’ that is never realised.” Sir Mo Ibrahim, a Sudanese-British businessman, adds: “Unmet expectations, especially for the young people, fuel frustration and anger, the best triggers for unrest and conflicts.”

Growing economies with lots of opportunities are not only good for civic calm; they are also vital to withstanding climate change. The un Economic Commission for Africa says that 17 of the 20 countries most vulnerable to climate change are in Africa. In 2024 droughts and floods associated with the El Niño phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a flip-flopping tropical-weather phenomenon, showed how vulnerable farmers’ livelihoods are to climate extremes. Floods displaced 4m people and closed thousands of schools. The World Meteorological Organisation, a un agency, has estimated that African countries divert up to 9% of their budgets to deal with such shocks. If the global temperature rises more than 2°C above what it was in the 19th century African crop revenues could fall by 30%, according to a recent paper by Philip Kofi Adom for the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank based in Washington, DC.

But the foundations such growth would need are in disrepair. The IMF says that about half the countries in Africa are experiencing “high macroeconomic imbalances”, by which it means one or more of the following: inflation at 50% or higher; a wide fiscal deficit; debt-service costs of 20% or more of government revenue; and foreign currency reserves that can cover just three months of imports.

Finance is increasingly hard to come by. Borrowing in dollars on capital markets is more expensive than in the 2010s. Foreign direct investment flows have fallen by about a third since 2021. In 2023 Chinese lending to Africa was $4.6bn, a rebound from paltry amounts at the start of the decade, but still below what was seen in every year of the 2010s. The share of Western aid flowing to Africa is declining.

There are other reasons to worry. Geopolitical tensions are at a post-cold-war high, and the IMF says sub-Saharan Africa is the region that would be hit hardest if the world split into separate trading blocs. Some policymakers also fret that the rise of automation will make it harder to attract the sort of labour-intensive manufacturing that powered Asia’s rise.

This special report will argue that, under a business-as-usual scenario, the Africa gap will not be closed. The continent’s countries need much greater levels of investment from Africans and foreigners alike. Most need larger, more dynamic private sectors, more productive farms and more effective governance. They need better provision of public goods and less graft. Only then can they expect the sort of productivity gains and economic transformation seen elsewhere in the emerging world.

For this to happen, those in power need to want it to happen. At present, this is all too often not the case. African elites are often frustratingly complacent about the future of the continent. There are exceptions, but for the most part this generation of political leadership is deeply uninspiring. African business leaders, for their part, are hobbled by political interference and thus incentivised to be damagingly short-termist. This can lead to mutual enrichment and a satisfaction with the status quo. But business- and politics-as-usual are failing today’s ordinary Africans—and blighting the prospects of those to come.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.