Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

How many international students is too many? – News

International students are essential to Australian universities and to our economy.

In 2024, just under 1.1 million international students were enrolled in Australia – that’s the highest number we’ve ever recorded.

Most (46 per cent) international students attend university, followed by vocational education and training (36 per cent), and ELICOS (13 per cent).

ELICOS stands for English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students. These are English language courses offered specifically for international students who need to improve their English skills. This can be a prerequisite for students who haven’t met the English language requirements of a course they’ve been accepted in.

But what share of a university’s student body should come from overseas? Is there such a thing as “too many” international students? This is a hot topic in Australian higher education and the broader housing affordability discussion.

We’re not alone in having this discussion. Canada, the UK, the US, and New Zealand are all grappling with the same balancing act – how to welcome students from abroad without losing the local character of campus life.

Is these such a thing as too many or too few international students on campus and in the country?

Why we welcome international students

Before we begin, a quick recap of why we import so many international students.

It’s a money maker. They pay much higher fees than domestic students and subsidise the education system. Each international student pays more than $30,000 in direct student fees each year and creates additional spending of roughly the same amount by consuming food, shelter, and traveling around the country as a tourist (often with their visiting parents in tow).

International students also boost university rankings. Global league tables like QS and Times Higher Education reward institutions with a strong international presence.

University is meant to be a time of the lifecycle where we are exposed to new ideas and open our minds to new worldviews. In that endeavour cultural diversity pays off. Classrooms become richer, more global learning environments.

Local students are meant to benefit from exposure to new cultures and worldviews. International students gain experience in a new system.

In a globalised world, these are powerful positives that we want to benefit from. But as with so many good things, more isn’t always better.

Too much of a good thing?

Having too many international students can backfire. One of the biggest concerns is social self-segregation, where domestic and international students form separate bubbles.

That starts with housing – international students often book purpose-built accommodation from overseas as their parents don’t want their 18-year-old babies house-hunting in our overheated markets. International students typically arrive on campus weeks before locals to allow them to acquaint themselves with the new surroundings.

While well-intentioned, this means they form early bonds before domestic students even show up. Since most uni friendships form in the first fortnight, this timing entrenches social silos.

Interestingly, research suggests students feel more isolated in “perfectly balanced” (50:50) classrooms than in cohorts skewed one way or another.

Large international student numbers also get blamed for housing shortages and overstretched services. While they mostly occupy purpose-built student housing (a niche market), that housing is still built by the same scarce workforce as the rest of our residential supply.

Then there’s the academic impact: studies show that high proportions of international students can slightly reduce outcomes for domestic peers. Differences in learning styles and language barriers are listed as causes.

All this suggests there’s a tipping point. Beyond a certain percentage, the benefits of internationalisation might start to unravel.

The sweet spot

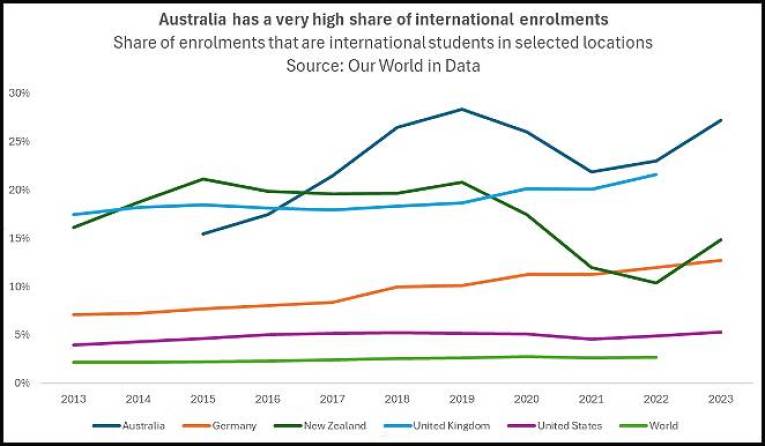

So, what do the experts say? Many suggest a “healthy” international share sits somewhere between 15 per cent and 30 per cent of the total student body – Australia currently sits at the upper limit of that.

That’s enough to enjoy the benefits of a global classroom without overwhelming the local experience. Some big players, like the University of Sydney, are closer to 50 per cent.

Vice-chancellors from Deakin and RMIT have publicly called for a voluntary cap at around 35 per cent, warning that social licence may fray above that level. That seems like a plausible limit considering the experience in other countries.

Canada faces similar housing pressures and recently introduced a temporary cap. British Columbia is looking at a 30 per cent ceiling for international enrolments in public institutions.

In the United States, international students make up only about five per cent of undergrad enrolments. In some elite institutions like Columbia (~30 per cent) and Carnegie Mellon (~40 per cent) the share is higher.

Elite institutions in the United Kingdom attract international talent at high rates. Oxford sits around 33 per cent, Cambridge around 40 per cent and the London School of Economics tops the chart at 70 per cent.

No national cap exists, but former British Universities Minister Jo Johnson warned against locals feeling outnumbered. The government in Singapore took a proactive approach, reducing international shares to 15 per cent to protect opportunities for locals.

The emerging international consensus? Around one-third international enrolments is the unofficial upper limit.

The devil is in the detail

It’s not just the overall share that matters as context matters. In postgraduate STEM fields, it’s common (and often beneficial) for half or more of students to be from overseas.

These hyper-specialised fields can be utilised to create a local workforce. We deliberately educate postgrads in fields that we desperately need workers in and try to entice them to remain in Australia after graduation.

In other subjects like a teaching degree, a high international share might feel out of place.

And even in a “perfectly balanced” classroom, things can go wrong: University of Sydney surveys found domestic students reported more isolation than international students.

The newcomers had strong peer networks. The locals felt like the odd ones out. As Dr. Michael Spence (University of Sydney VC) noted, 50:50 mixes sometimes performed worse socially than lopsided ones.

The Goldilocks Rule of International Enrolments

Here’s the simplified takeaway:

- Below 10 per cent: You’re probably missing out.

- 15-30 per cent: That’s where most experts agree the benefits outweigh the costs.

- Over 35 per cent: You’re pushing into risky territory (especially if the international cohort isn’t well integrated).

- Over 50 per cent: Even the most enthusiastic internationalisation advocates call this excessive (with exceptions for specialist postgraduate programs).

Percentages alone don’t tell the full story. The quality of campus life, strength of support services, and genuine interaction between local and international students are just as important.

The answer isn’t just numeric. Universities need to engineer meaningful interaction across cultural lines and must be held accountable for the outcomes.

Over the past year, the federal government has introduced a series of policies to curb the rapid growth in international student numbers.

A national cap of 270,000 new international enrolments was introduced for 2025, with quotas for individual universities. Student visa fees almost tripled to $2000 by July 2025.

Eligibility requirements have also tightened, with higher English language standards, increased financial thresholds, and stricter assessments of applicants’ intentions.

Post-study work rights were scaled back, especially for older graduates, and it’s now harder for international students to shift between visa types while staying in Australia.

The government has also cracked down on so-called “ghost colleges” (or “degree mills”) and introduced slower visa processing for institutions nearing their student caps.

These measures, taken together, signal a clear intent to reshape the international education sector towards smaller, higher-quality cohorts.

I would expect international student numbers to more or less end up balances somewhere around the one million mark. The housing market will react by building purpose-built student accommodation.

The building boom in international student housing won’t last forever since a somewhat stable population is constantly being refreshed with new students who move into the same apartments.

On a national level it seems that Australia will sit on the upper end of the Goldilocks Zone. Individual educational institutions are now in the spotlight.

They must be much more proactive in integrating international students into the social fabric of campus life. Taking a more proactive approach in housing local and international students together (think dorms on US campuses) might be worth exploring.

Simon Kuestenmacher is a co-founder of The Demographics Group. His columns, media commentary and public speaking focus on current socio-demographic trends and how these impact Australia. His podcast, Demographics Decoded, explores the world through the demographic lens. Follow Simon on Twitter (X), Facebook, or LinkedIn.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.