Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

What science says about sarcasm: To understand it, you need to have street smarts | Science

“Mom, can you get me a glass of juice?” a young woman comfortably asks from the sofa. “I didn’t know you broke both legs,” her mother sharply fires back, criticizing her daughter’s laziness.

Sarcasm is incisive and demanding. It strains irony to its bitter point, almost always to question or mock. Understanding it requires engaging multiple neural connections at once and knowing how to adapt to the context, which is why scientists study it with particular interest in mental and neurological disorders.

Until recently, what was known about this type of biting humor referred only to its use in English. However, Argentine scientists recently published the first preliminary results in relation to the Spanish language, confirming that understanding sarcasm is a demanding exercise for the brain. One of the objectives of the study is to determine whether the inability to comprehend sarcasm can be a reliable indicator in the diagnosis of neurological pathologies and mental health problems.

“I think we’ll be able to provide that answer within a year,” estimates Bautista Elizalde Acevedo, one of the study’s authors. He’s a doctor in Biomedical Sciences and a researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina (CONICET). The scientists are working on this study with the hope of applying it to patients with schizophrenia, who often have trouble identifying sarcastic situations, idiomatic expressions, or prosody — messages whose meaning is determined by the tone of voice — among other forms of pragmatic language.

The research is also innovative: it uses a simple method of displaying realistic situations in comic book format, created entirely by the researchers. The experiment in Spanish ultimately showed more extensive neural connections than those conducted in English.

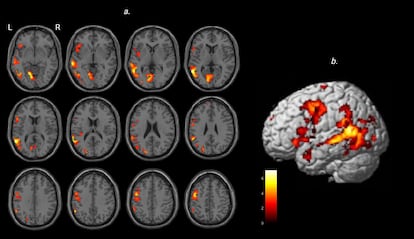

This study — unlike previous ones — showed the activation of a very extensive brain network. “This is what distinguishes it from other studies that have been done. We don’t know if it’s because we did it in Spanish, or because our test had a lower cognitive load than the tasks applied by others.”

“In those cases, a lot of prior information was required to reach the sarcasm stimulus, while ours was more direct and better imitated real-life situations,” says Nicolás Vassolo, the lead author of the study. “In a simple image with simple text, simultaneously, we already had a stimulus that contained something sarcastic,” adds Vassolo, who has a degree in Psychology and is a researcher at CONICET.

When interpreting sarcasm, multiple brain regions with neural connections related to social skills are activated simultaneously.

Sarcasm uses irony and double entendres, which requires being able to understand how another person is thinking and in what tone they’re speaking. Scientists call this cognitive ability — comparable to empathy — “theory of mind” (ToM).

“It’s not telepathy; the person understands where the conversation is going based on the context, the face they make and what they’re saying to you,” explains Mariana Bendersky, another of the study author. “This is what sarcasm requires. If you don’t have this understanding, you’re lost. You take everything literally: you may take it the wrong way or the right way, but you didn’t understand that they were pulling your leg,” adds Bendersky, a medical doctor and the artist in charge of illustrating the comics for the experiment.

Language — as explained by Lucy Alba Ferrara, a doctor in Neuroscience and researcher at CONICET — “has a very succinct processing [system] in the brain, with very important nodes that are repeated.” When this type of humor is processed, these nodes are joined by others that are more variable and much more dispersed, scattered throughout the cortex.

This is due to the overlap of sarcasm with other skills linked to the theory of mind, as well as the contextual information involved in the correct interpretation of information. “That’s why the neural correlates of sarcasm are so interesting,” Ferrara points out.

This complexity is one of the reasons why language models based on artificial intelligence have such a hard time capturing sarcasm. They don’t achieve the same level of complexity as the neural connections that produce interpersonal skills.

A similar problem is seen on social media. Without context, gestures, or tone of voice, interpretation falls prey to literalism. “The word is there, so they can guess what it means. It can be interpreted in any direction,” says Bendersky. “On top of that, it significantly impoverishes the language, because the message is very short, somewhat telegraphic, limited in character count and not very flowery. When you read it, you feel that their language and grammar are deteriorating. If we consider that this also shapes the brain, it’s worrying.”

The scientific team will continue to delve into the brain to compare the findings of this study with what happens in patients with schizophrenia. “Now, we want to survey a group where the function appears altered directly in behavior — not just in the brain — and, in that way, compare the two samples: healthy brains and brains with some type of pathology,” Elizalde explains.

Still, putting aside mental illnesses, being healthy isn’t enough to grasp sarcasm. You need wit, street smarts… and as the song La Bamba goes, “un poco de gracia” — a little bit of grace.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.