The purpose of this long journey? Buy avocado saplings.

Back in 2018, Singh had planted a few avocado plants alongside longan and pecan nut trees—all exotic things. The avocado trees are now bearing fruit and selling at a premium. Visitors to his farm pay as much as ₹150 apiece.

So, Singh is now planning to uproot the lemons and guavas, planted in three acres at his farm, and replace them with avocados.

It was an expensive affair. Singh spent nearly ₹7 lakh on 800 saplings and in transporting the plants, a feet long, to Punjab. Now, he wants to sell 200 saplings to other growers and plant the rest.

“I am expecting a yield upwards of 40 kg per plant after four years and a price of ₹150-200 per kg,” Singh said. That would translate to an income of close to ₹400,000 per acre, net of all expenses. Of course, as is always the case with farming, there are a few unknowns. It remains to be seen how the plants adjust to the temperature extremes in Punjab where it often touches 47 degrees Celsius during the summer and close to zero degrees in the winter. The price Singh receives will also depend on how domestic production grows in the coming years and the price trajectory of imported fruits.

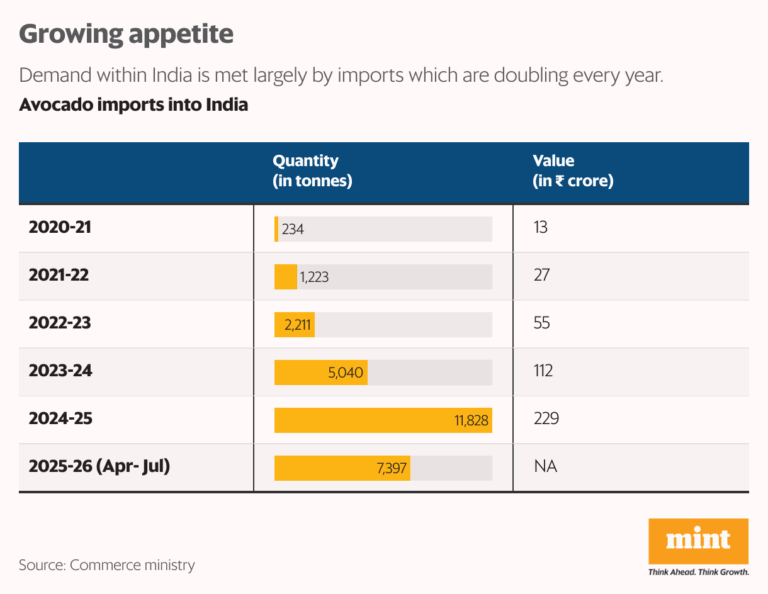

Between these unknowns, one thing is certain: the growing appetite of Indian consumers for avocados. Currently, demand within India is met largely by imports which are doubling every year. In FY24, India imported 5,040 tonnes which climbed to nearly 12,000 tonnes in FY25. This year, the imports are likely to cross 20,000 tonnes (the imports during the first quarter of FY26 was nearly 7,400 tonnes). Come to think of it, a few years back, in FY21, imports were a mere 234 tonnes.

Avocado-dosa

So, what is fueling demand within India? It started as a post-covid-19 pandemic health and nutrition trend and has since turned into a staple for upper income households, said Vernika Awal, a Delhi-based food writer and consultant. From street vendors to upmarket cafes, avocados are being served on toasts and in shakes. In most big cities, the fruits are available in neighbourhood markets. Avocados have gained a reputation as a heart-healthy superfood, packed with nutrition—a mix of healthy fats, fiber, vitamins and antioxidants.

“I remember first having guacamole (a dip made of mashed avocados seasoned with lime juice and other ingredients like onions, tomatoes and jalapenos) way back in 2013 while visiting Chile. Now a vegetarian sushi will be invariably prepared with avocados replacing the salmon inside,” Awal said.

Apart from social media and fitness enthusiasts who played a significant role in popularizing avocados, chefs played a part too, partly driven by the reality that to charge a premium for a vegetarian dish one has to use expensive ingredients, like avocados, exotic mushrooms or zucchini.

While the upwardly mobile of today have taken to avocados, the fruit finds a mention in India’s culinary history. A few years back, Awal recalls that she stumbled on makkhan fal or butter fruit in the recipe book of the Maharaja of Patiala from a century ago. It recommended eating the oily fruit with a sprinkle of salt. “It was exotic then too, so was eaten as it is for the novelty factor.”

View Full Image

Avocado on toast. (Nandita Iyer)

At the Omo, a vegetarian restaurant in Gurugram, the crispy avocado dosas are a hit. “Years ago, I had a dosa with avocado filling sold by the roadside in Vattakanal in Tamil Nadu. So, after joining Omo, I replaced the spinach and corn filling with mashed avocado. Everyone loves it,” said Chetna Chopra, the culinary director at Omo.

Apart from the dosas, the restaurant serves avocados on sourdough toasts, as a starter with beans, and adds the fruit for a creamy texture in smoothies and chocolate mousse.

Chopra adds that customers love to hear that a dish is prepared with avocados. “They are ready to pay a premium for such items. The fact that the fruit has no allergens attached to it adds to its appeal.”

It’s not surprising that the dosa served in Vattakanal in Tamil Nadu used avocados for the filling. In fact, avocados have been grown in India for over a century now, in hilly regions of south India like Kodaikanal, Ooty, Wayanad and Coorg. They were known as butter fruit and consumed locally, often with sugar sprinkled on sliced fruit.

Avocados most likely came into India via Sri Lanka and were introduced by the Christian missionaries in the early 1900s, said Muralidhara B.M., head of the Central Horticultural Experiment Station at Chettalli, Coorg.

Avocados have been grown in India for over a century now, in hilly regions of south India like Kodaikanal, Ooty, Wayanad, and Coorg. They were known as butter fruit and consumed locally, often with sugar sprinkled on sliced fruit.

But Indians who are fond of either sweet or sour fruits did not take to ‘tasteless’ avocados. So, it remained limited to a few local growers in the hilly areas of the Western Ghats. Muralidhara, a fruit scientist who did his PhD on avocados, explained that globally, avocados come from three distinct races: Mexican, West Indian, and Guatemalan. The varieties first grown in India were green-skin West Indian types, which have a low-fat content and lower shelf life compared to famous varieties like the Hass which has a longer shelf life and high fat content (over 15% by weight).

With the growing popularity of avocados, the Chettalli research station began working on avocados and released two new varieties in 2020: Arka Coorg Ravi and Arka Coorg Supreme. That’s what brought Singh (the farmer from Punjab) to Coorg to procure saplings. So far, the institute has sold planting material for nearly 1400 acres to growers from Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh.

Aztec’s testicle

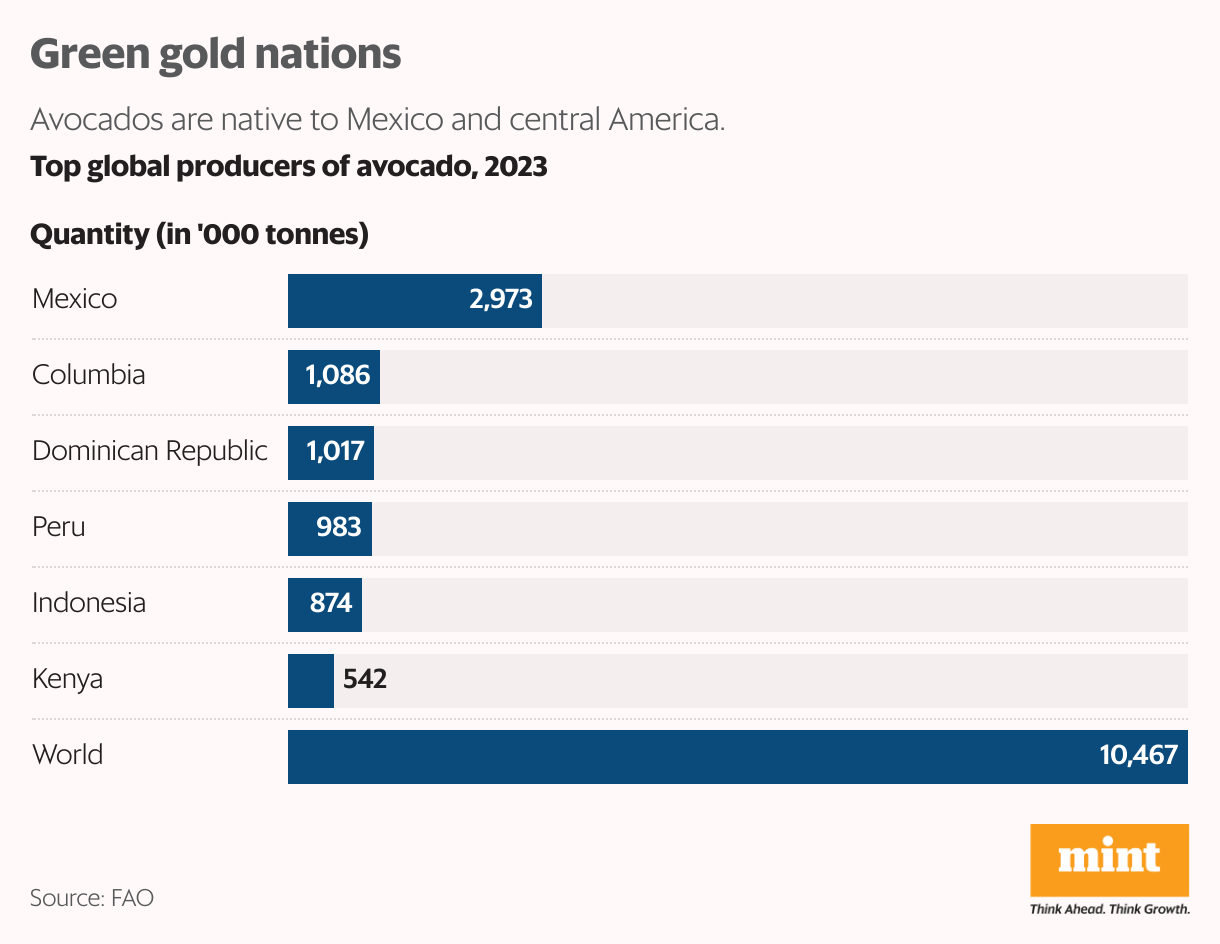

Avocados are native to Mexico and central America and are believed to have been domesticated more than 10,000 years ago. The Spanish conquerors discovered the pebbly fruit in the 16th century and introduced it to the rest of the world. Its global popularity, however, followed the interest of a bunch of growers from California, US, who coined the name avocado in 1915. Originally, the fruit was known as ahuacate, the Aztec word for testicle (another name was alligator pear as the fruit’s skin resembled that of an alligator). Ahuacate was hard for Americans to pronounce and alligator pear was not an appealing name for a fruit. Therefore, avocado!

Hass, the most popular purple skin variety grown and consumed globally, was developed from a chance seedling in 1926, by a postal worker named Rudolph Hass. But the global penetration of avocados happened because of concerted marketing efforts of grower groups, both from California and Mexico. Hass became the preferred variety because of its long shelf life—about 10-15 days after plucking which can be extended by months in a cold store. This made it suitable for long journeys across the globe.

As per a June 2025 estimate from Rabobank, the global avocado market is around $20.5 billion. The report estimated that global avocado exports are likely to touch 3 million tonnes by 2026-27, from one million tonnes in 2012-13.

Today, India imports about 90% of the avocados it consumes from Tanzania (as the produce is duty free), with smaller volumes coming from Australia and Kenya, among others.

But slowly, home grown Hass is likely to replace a part of the imports. Westfalia Fruit, a leading grower and exporter of avocados globally opened a nursery in Coorg in 2020 to promote domestic cultivation of Hass avocados.

Nestled among coffee estates and lush forested hills of Coorg, the 50-acre nursery and demonstration plot now supply over 30,000 saplings every year. Its largest clients are coffee and tea estates (including the likes of Tata Coffee) looking to diversify into the high value crop. So far, it has partnered with growers for over 800 acres of avocado planting area.

View Full Image

Avocado harvesting in progress at the nursery of Westfalia Fruit India in Coorg, Karnataka. (Sayantan Bera)

“Three years from now, the domestic Hass avocado market will be about 35,000 tonnes with close to 5,000 tonnes coming from local growers,” said Ajay T.G., general manager at Westfalia Fruit India, which is also the largest importer of Hass avocados into India. “Avocados will become like the Kiwi which is a 60,000 tonnes market now,” he added.

Growing round the year also means that cafes and restaurants are now able to place avocado dishes on their menu. Ajay also highlighted an interesting aspect of avocado consumption. During India’s mango season (April to August), consumption of every other fruit takes a hit, but not avocados. Which means consumers are using the fruit differently, as part of their breakfast, salads and regular meals—and not exactly the way a fruit is consumed.

“We are now looking to launch avocado puree and ready to eat guacamole in the Indian market to serve both quick service restaurants and consumers,” he said.

A buttery bet

On a visit to Coorg in October, Mint met a few growers who are betting on avocados. Among them was Akshath Muthanna, a third-generation coffee grower from south Coorg. The 24-year-old did his background research before diverting five out of 65 acres of coffee plantation into avocados. Muthanna procured the saplings from Westfalia with a promise of a buyback when the trees start yielding.

View Full Image

Akshath Muthanna, a third generation coffee grower from south Coorg, has diverted five acres from coffee to avocado, hoping for higher returns. (Sayantan Bera)

“In my neighbourhood, I am the first to give it a shot. My estimates suggest that net return from avocados could be anywhere between ₹6-8 lakh per acre, compared to ₹3.5-4 lakh for coffee,” Muthanna said during a meeting at his ancestral bungalow adjacent to the coffee estate. He also showed off the first fruit: a dark-skinned Hass which is yet to ripen. For the family, avocados are the latest venture after coffee, pepper, areca nut and a couple of hotels.

In the tourist hub of Madikeri in Coorg, coffee grower D.M. Kumar is also banking on avocados. After burning his hands with an exotic flower (Anthurium) which led to large losses during the pandemic, Kumar planted 3.5 acres with Hass avocados. “I chose Hass over other varieties because of its longer shelf life. The demand within India is growing but I am also worried if these current prices will sustain as production increases,” Kumar said.

He warned new growers to be careful while buying saplings. “The quality of rootstock (from which saplings are developed) is important. Many buyers come from other states and purchase saplings from small nurseries. They may be in for a shock after 4-5 year when the trees do not yield properly,” he added.

View Full Image

D.M. Kumar, a coffee grower from Coorg, suffered huge losses with anthurium plantations post-pandemic. Now, he is experimenting with avocado in a 3.5 acre plot. (Sayantan Bera)

When compared to Kumar and Muthanna, some are taking outsized bets. For instance, Prabhu Gowda, who runs an IT services firm, returned to Bengaluru in 2018 from the US. Following his unmet passion for farming he narrowed down on avocados. Together with his partner, Gowda bought 47 acres in the outskirts of Bengaluru to grow Hass. “We plan to supply the top-grade fruits for table purpose and extract oil from the rest,” Gowda said. A kg of Hass can yield 300 ml of oil which retails at over ₹2000 per litre.

Despite the growing popularity of avocados among farmers, it’s only the well-off who are getting into it. The reason is simple: for orchards to yield a remunerative return, it takes 4-5 years from planting. The costs range from ₹4-5 lakh per acre (apart from the land cost). Just one sapling of avocado can cost anywhere between ₹800 to ₹2,500 (about 150 saplings can be planted in an acre) depending on the variety and rootstock.

One drawback of Hass is that it cannot tolerate temperatures beyond 35 degrees Celsius. Which is why this variety is being tried in the temperate climates of southern hill stations. But there are other varieties like Pinkerton and Ettinger which are more suited to hotter regions.

Harshit Godha, whose bio on Instagram reads “probably the most handsome avocado farmer in the world”, is promoting heat-tolerant cultivars from his nursery in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. While studying at UK in 2017, Godha was taken in by avocados imported from Israel, primarily because of his interest in fitness and nutrition. After months of hand-on training in Israel, he now imports rootstocks from Israel and has so far sold over 15,000 plants to farmers from Gujarat to Arunachal Pradesh.

“It did not take me long to understand that this could be a profitable crop for Indian farmers looking to diversify,” Godha said. “This is not a fad that is going to go away.”

The history of food is replete with examples where an exotic fruit or vegetable has graduated into a staple. Come to think of it, some of the most common items in the Indian diet, be it tomato, potato or apple are not native to India. Could avocado be the next such item? But then, the avocado toast sold by an upmarket eatery for a premium may lose its charm.

Key Takeaways

- Driven by soaring consumer demand, India’s avocado imports have doubled annually, with volumes expected to cross 20,000 tonnes in FY26

- This has presented a significant market opportunity for local growers

- Indigenous avocado cultivation, historically limited to south India’s hills, is now expanding nationwide as farmers seek higher profits than traditional cash crops like coffee

- Projected net returns from avocados are extremely high, with estimates up to ₹4 lakh to ₹8 lakh per acre, making them far more lucrative than established crops like coffee

- A horticultural research centre in Coorg released two new varieties in 2020: Arka Coorg Ravi and Arka Coorg Supreme

- Orchards take a long time to become commercially viable, with a remunerative return only expected 4-5 years from planting

- This requires significant capital to sustain the venture

- In addition, the most popular global variety, Hass, struggles with India’s extreme temperature variations, requiring new growers to choose special heat-tolerant cultivars

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.