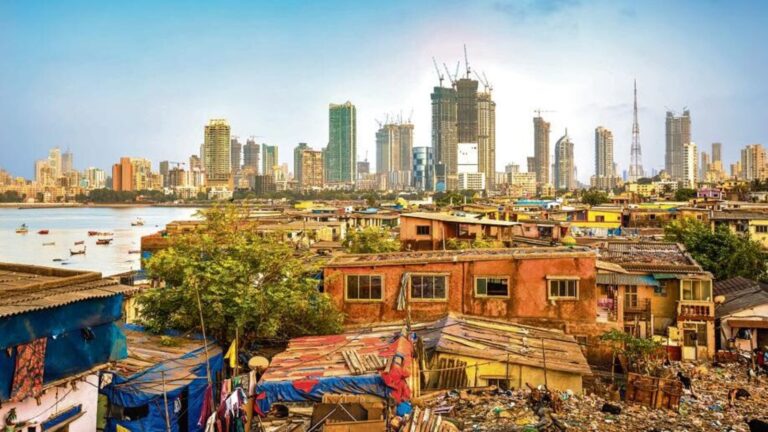

In this piece, I detail three measures to strengthen local governments, unlock more effective planning and governance, and ensure India’s urbanization translates into better outcomes for all.

Reorient MoHUA and state urban departments for local governance and regional development: At present, the ministry of housing and urban affairs (MoHUA) dedicates most of its resources and efforts to disbursing funds to states and urban local governments (ULGs or municipalities) through Finance Commission grants and missions such as AMRUT, Swachh Bharat and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana.

This has made it, in effect, a schemes-and-infrastructure ministry, rather than one focused on the planning, economy and governance of cities.

MoHUA also oversees organizations such as the Central Public Works Department, National Buildings Construction Corp (NBCC) and the Delhi Development Authority, all of which follow mandates that mostly relate to infrastructure and service delivery, not governance. However, MoHUA’s department of local self government, which was envisaged to strengthen urban local self-governments, remains all but defunct.

By contrast, rural India has the ministry of panchayati raj (MoPR), whose principal mandate is to strengthen panchayati raj institutions and, through them, local governance systems and processes in villages. MoPR is distinct from the ministry of rural development, which focuses on schemes covering rural employment, housing and roads.

To make MoHUA fit for purpose, it should be reorganized along two dimensions:

First, a regional/typology focus: Efforts must be adapted to the diversity of our cities, which range from metropolitan areas (with 4 million-plus populations) and cities in large urbanized states (Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat) to those in large less-urbanized states (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal), small urbanized states (Goa), small less-urbanized states (Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh) and hill states (Uttarakhand and Northeast states).

This would lead to greater place-based specialization and an integrated approach across the three Es of economic growth and job creation, environment sustainability and equitable access to opportunities, urban infrastructure and services, unlike the current approach, which over-indexes urban infrastructure.

Sectoral expertise needs to be deployed as well. Specialized divisions in critical infrastructure areas such as mobility, water and sanitation and housing should be staffed with an adequate number of empowered subject-matter experts, rather than token advisors. This would differ from the current way that sectoral schemes are handled.

These principles apply to state governments as well. Many states have separate departments for housing and urban planning and for municipal administration, with development authorities and parastatals under the former while municipalities report to the latter. This creates further avoidable fragmentation.

Adopt a differentiated approach to governance for metropolitan, emerging and small cities: Urban governance in India remains largely one-size-fits-all at both the Union and state levels. Yet, the 2011 Census reveals a clear pattern: we have 45 cities with populations above 1 million; 470 cities with headcounts between 100,000 and 1 million, and about 4,000 small cities with fewer than 100,000 residents. Each of these three categories hosts about one-third of the country’s urban population.

Despite stark differences in the planning, governance, infrastructure and financing needs of cities across these three categories, the legal framework, schemes and missions that serve them are by and large the same, with minor variations. This mismatch underscores the need to adopt a differentiated approach to urban governance based on city type.

India’s largest cities urgently need a metropolitan governance paradigm. The draft Greater Bengaluru Governance Bill proposed by the Brand Bengaluru Committee (rather than the diluted enacted version) is worth studying as a potential model. For emerging and small cities, districts can be leveraged as units of governance to achieve rural-urban convergence, integrate economic and environmental planning and governance, and coordinate shared capacities and services through municipal shared service models.

Such an approach would leverage India’s unique spatial pattern of urbanization, since half of our urban population lives within 60km of the 45 million-plus cities.

While districts have elected governments under the panchayati raj system, no equivalent exists for ‘nagar raj.’ District planning committees, which are constitutionally mandated to consolidate rural and urban plans, therefore need to be reactivated.

Create and publish a framework for a model rural-urban transition policy: Another area that demands urgent attention is the transition of rural areas into urban centres. About 24,000 large urbanizing villages in India, home to 190 million people, are governed under panchayati raj institutions even though they may exhibit urban characteristics.

Further, 971 new ULGs have been created since 2011 without rural-urban transition planning. Too often, the switch is determined by the stroke of a pen, without serious consideration for the loss of rural welfare schemes, the status of master plans, institutional continuity or its impact on taxes and user charges.

We need a model rural-urban transition policy that addresses these challenges. It would help plan for continuity in fiscal transfers, safeguard service delivery and enable integrated infrastructure planning as villages evolve into towns. Odisha has shown the way by notifying such a policy in 2023, offering a potential template for other states.

Taken together, these three measures would give India’s cities what they currently lack: stronger local governments, institutions built for their scale and diversity, and a planned system for managing urbanization.

Only by putting local governments at the centre of urban policy can India ensure that we achieve the vision of Viksit Bharat by 2047 for all our cities and citizens.

The author is CEO, Janaagraha.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.