Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

Living in Japan — an exchange student’s view: Time and seasonality (Pt. 2)

The author views plum blossoms for the first time after rushing to Yushima Tenjin Shrine in Tokyo. “March and April were like nothing I’ve experienced before,” she says.

When I came to Japan, I brought with me a stack of various academic interests: U.S.-Japan relations, democratization, constitutional law, and political thought. As a student of international relations, I was more than eager to understand Japan’s role on the world stage. My coursework was nothing less than full of theories of power, global structures, policy, and diplomacy. But being here, I gained a perspective extending beyond geopolitics.

I also carried with me expectations others had told me about studying abroad: that my time here would be fast and exciting. Telling others I came to Tokyo to study, there was this sense that my time was limited. “Make the most of it,” I was told. “You only have a year. Go everywhere, try everything, make it count.” Things like taking photos at shrines, eating ramen, going shopping at Donki (as the discount store Don Quijote is familiarly known), playing at Tokyo Disneyland, traveling as much as possible, and experiencing the curated fantasy of Japan sold in study abroad brochures — maybe to some, studying abroad should feel like an extended vacation with classes added in. It was expected I would return home with souvenirs and some insight into global and regional diplomacy.

Instead, what has changed me the most during my time here has not been what I saw or what places I ticked off a checklist, but what I learned to notice. I marked time not by my deadlines or upcoming holidays, but instead by an awareness of the rhythm of the seasons, or “kisetsukan” in Japanese.

Seasonality in Japan and the US

Coming from California, where winters are marked by a few days’ rain and the rest of the year is sunny and mild, the only indicators I had of the change of time were consumer events and holidays: the arrival of summer vacation, Halloween and Christmas, fireworks during New Year’s Eve, a day off of school for Memorial Day weekend, or Black Friday sales after Thanksgiving in November.

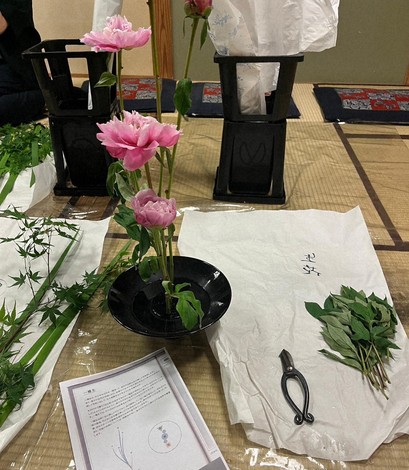

This photo shows an ikebana arrangement. The author says she can experience how the world around her changes through her ikebana circle.

In contrast, I can recall each season of my life in Japan not by what exams I had coming up or what holiday I was desperately awaiting, but by my surroundings. I remember the illuminations during Christmas time and the carp banners in May. I remember what months I started seeing more tour groups in Harajuku and when the humidity started to rise again. I noticed the arrival of autumn leaves, cherry blossoms, hydrangeas, the rainy season, and the sound of cicadas.

At my university’s ikebana club, each week I could see the little ways in which the world changed through what we used for that week’s arrangements: carnations, curly willow branches, blooming peonies, wreaths of evergreens. I began to notice that people I talked to would mention a particular flower blooming, or say things like, “It’s starting to feel like summer.” Living here, I started to anticipate these shifts too — learning, slowly, to see time differently. It’s how nature, meals, and feelings are tied to the shifting rhythms of the year. I think I gained a very different sense of “seasonality” that I didn’t have at home.

Time, politics, and cultural understanding

The author enjoys her first viewing of the autumn leaves after the arrival of fall, at Rikugien Gardens in Tokyo.

Japan, from my perspective as an international student, essentially gave me a new clock to leave with. I came to Japan to study diplomacy, borders, and macro-politics. As a student of global affairs, I often study overarching global systems and fast-changing events. But what I learned living in a foreign culture has informed my thinking in a different way. It didn’t just give me a new perspective on Japan; it helped me recognize how America’s emphasis on productivity and consumption shapes even how we experience time. It has reminded me that culture is as essential to international understanding as policy is. Sometimes, it can even come down to just learning how another society eats, moves, marks time, and finds meaning.

In our time of accelerated globalization, where cultural exchange is often reduced to tourism and superficial fusion, learning to inhabit the temporality of another place — its rhythms, its rituals, its markers of change — seems to be one of the most intimate and transformative forms of cross-cultural understanding and exchange to me.

(By Kacey “Kei” Douglas)

Profile:

Kacey “Kei” Douglas

Kacey “Kei” Douglas is originally from San Francisco, California. She has been studying international relations, political science, and economics in Japan since 2024. She is currently participating in a study abroad exchange program between her home university in California and her host university in Tokyo. Her interests are in the Asia-Pacific region, comparative politics, and constitutional law.

(This is Pt. 2 of a series. Subsequent parts will be published intermittently.)

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.