Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

‘The animal disappears from view’

An amazing creature that lives deep in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean was captured in time-lapse photographs, allowing scientists to learn more about the role it plays on the seafloor.

They found the small endomyarian anemone is perhaps the most prevalent animal on the Porcupine Abyssal Plain — making up about half of megafaunal density — and studied its feeding and burrowing habits. It lives 4,850 meters below the surface, and its diet includes a much bigger polychaete, or marine worm. The beings also spent hours creating new burrows.

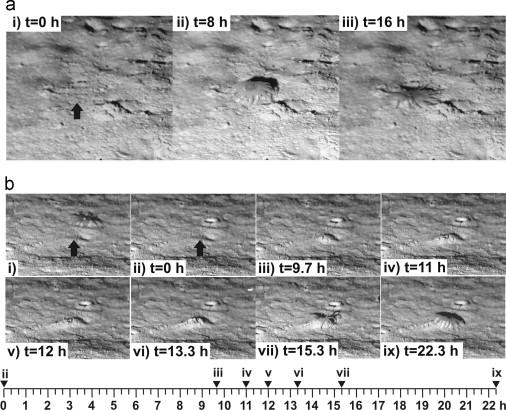

“In each burrow move, the animal disappears from view by retreating into its burrow, then a small mound appears a short distance from the original burrow,” the researchers wrote, as Discover Wildlife reported.

“This mound grows and is broken along the crest before the animal emerges from the apex of the mound, tentacles first, and establishes itself in the new burrow with its disk flush with the sediment surface and tentacles extended,” the study continued.

Photo Credit: Jennifer M. Durden, Brian J. Bett, Henry A. Ruhl

The study was published in Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. It followed 18 specimens over 20 months at eight-hour intervals and one individual over two weeks at 20-minute intervals. The RRS James Cook and RRS Discovery used towed-vehicle cameras to take 29,016 usable photos.

One anemone reached 109 millimeters (4.3 inches), while the average oral disk diameter was 32 mm (1.3 in). They have 24 tentacles.

Watch now: Giant snails invading New York City?

The creatures not only feed on phytodetritus from the seabed but are also predators, which is contrary to previous thought. The researchers said Iosactis vagabunda, which they called “dominant” in the title of the paper, is not a suspension feeder or even an opportunistic omnivore but a “significant” predator.

In one instance, a 22-mm anemone spent three-plus days on camera before it ate a 105-mm polychaete over 16 hours. It spent the next 56 hours fully extended above its burrow, stretching to that maximum length of 109 mm. The chaetae, or bristles, of the worm “were visible through the body wall of the anemone,” per the study.

The anemones observed spent 19 days in their burrows on average, and the scientists tracked one individual for nearly 10 days. In one sequence, it took 22 hours to move to a new burrow.

After disappearing from view, it started building a mound from under the sediment nearly 10 hours later. It did that for almost five hours until breaking through, and it took eight more hours to emerge and establish itself. It spent six days there before moving again.

“This hemisessile lifestyle, with frequent burrow relocation, may be to allow more effective exploitation of resources and thus be linked to feeding behaviour,” they wrote, noting the invertebrates’ movement was unique among predatory anemones in the Porcupine Abyssal Plain, as others are immobile.

The researchers said the anemones may be “critical” carbon cyclers, as their observations showed an impact two to 20 times greater than another study of sea anemones at the plain.

This and similar discoveries, including seagrass’ heavy metal sequestering potential, prove the value of scientific exploration of the ocean.

Amid rising global temperatures, seawater is absorbing much of the atmosphere’s excess heat, revealing the consequences of humans’ burning of dirty energy sources — and what can be done to rebalance Earth’s ecosystems.

Join our free newsletter for good news and useful tips, and don’t miss this cool list of easy ways to help yourself while helping the planet.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.