Our Terms & Conditions | Our Privacy Policy

There Is No Such Thing as Alternative Careers for Ph.D.s (opinion)

Pursuing a tenure-track faculty role isn’t the only option for Ph.D. graduates.

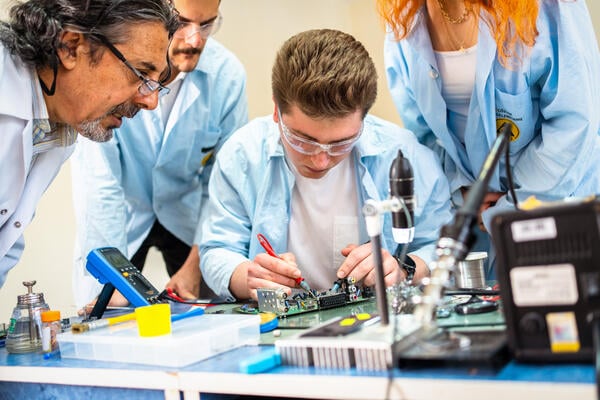

Phynart Studio/E+/Getty Images

Alt-ac. Alternative careers. Academic vs. nonacademic. Academia vs. industry. Going to the dark side. Selling out. Leaving academia.

For those pursuing or who have earned a Ph.D., as well as those who teach and mentor doctoral students, these phrases and terms still persist in academic environments. The concept of an “alternative” career no longer holds weight, though, and by continuing to use such language, we do ourselves and others an enormous disservice. In reality, there is no single “correct” path after earning a Ph.D.—it equips you for a diverse range of career opportunities.

Reality and the Data to Back It Up

Over the last few decades, the landscape of career options for Ph.D.s—no matter the discipline—has changed quite dramatically. For much of the 20th century, most Ph.D. recipients both expected and went mainly into tenure-track faculty roles in academia. In the latter half of the century, though, for a variety of complex reasons spanning better economic prospects, globalization and more, the numbers of doctoral recipients increased greatly; from 1958 to 1998, the number of doctoral recipients in the States quintupled.

However, there was no increase in the number of tenure-track faculty roles in academic institutions to keep pace and meet the demand of these new doctorates on the job market. There have been multiple organizations that analyzed changes in the various faculty appointment types in the States. This study by the American Association of University Professors showed that between 1987 and 2021, tenure-track faculty roles dropped from 39 percent to 24 percent, with a concurrent rise in non-tenure-track, contingent faculty roles from 47 percent to 68 percent. As tenure-track faculty appointments became scarcer and thereby incredibly competitive—a trend that continues in today’s job market more than ever—people have sought and found opportunities elsewhere.

Well summarized in a now slightly dated article in Science, the U.S. National Science Foundation’s biennial Survey of Doctorate Recipients indicated that for the first time ever in 2017, the private sector was one percentage point away from employing the same number of Ph.D. holders as educational institutions. Collected and analyzed by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, the most recent report from 2023 shows that “the proportion of doctorate recipients with … commitments in industry or business in the United States more than doubled since 2003, comprising close to half (47%) of all 2023 doctorate recipient employment commitments.”

In the last 15 years or so, there have been excellent efforts in two main thrusts in response to this changing landscape:

- Collection of Ph.D. career outcomes data: Quite a few groups formed to streamline best practices for collecting Ph.D. outcomes data, in a valiant attempt to create shared systems and processes, allowing for more uniform data collection and analysis. This includes groups such as the Coalition for Next Generation Life Science, the Future of Research, the Council of Graduate Schools PhD Pathways Project and others. In addition, individual universities and schools have made great strides to collect comprehensive outcomes data for their doctoral alumni, a key step toward transparency and knowledge. As an example, as part of my role, I capture and track outcomes data for doctoral alumni from my school.

- Development of doctoral-focused career training programs: While there have been excellent investments in undergraduate career support for quite some time, career training programs for doctoral students were quite limited historically. In the last decade or so, several federal agencies created grants aimed at supporting academic institutions in launching programming that reflected the range of career options. This included the NIH’s Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training awards and the NEH’s Next Generation Humanities PhD Planning grants, among others. Philanthropies such as the Mellon Foundation and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund also launched similar grants, sometimes in partnership with a professional society. And thankfully, many universities started investing more resources and staff to build out doctoral-focused career and professional development efforts. Career offices aimed at graduate students and postdocs are now common at large universities. However, departmental culture on this issue can vary widely, affecting the level of support doctoral students receive in different disciplines so there is still more work to be done. Professionals in this field, such as myself and those in the Graduate Career Consortium, are dedicated to supporting career preparation and professional development in ways that treat all careers as equal and as equally important.

Why Language Matters

Despite decades of change, ample evidence represented in data and investments from both small and large organizations, the transformation of how we talk about career options for those with doctorates did not happen overnight, seamlessly or without challenges. In fact, both outdated language and frameworks are still prevalent in academic culture today.

During my own Ph.D. in the early 2010s, career options were often portrayed as very binary: Either become a faculty member or “sell out” to industry. Or I would hear faculty speak in derogatory tones about “alternative” careers. In one instance I vividly remember during a meeting on reaccreditation, one professor said very bluntly that we only train people to be scientists and everything else was a waste of time and resources. “Everything else” referred to any training and programs related to professional skills such as leadership, communication, mentorship, management and more.

While things have thankfully improved since then, there are still many terms that continue to linger that are inaccurate and exacerbate false narratives around careers.

- Negative connotations: Merriam-Webster has multiple definitions for the word “alternative,” including “different from the usual or conventional: such as existing or functioning outside the established cultural, social, or economic system.” In other words, “alternative” means outside of the norm or traditional and, for many, conveys a negative connotation. So, by labeling a particular career or set of careers as the “alternative,” we are consciously or unconsciously attributing a negative association with it that absolutely impacts how people view the options available to them. In addition, while perhaps true at one point in time, today’s data doesn’t show that one career is an alternative to another for many disciplines, so this language doesn’t hold up from a statistical perspective, either.

- False dichotomy: Using phrases like “academic vs. nonacademic” or “academia vs. industry” sets up career options as a false, binary choice. As someone who has worked in this field for over a decade, I can assure you that there is a vast array of careers available post-Ph.D. By adhering to this either-or fallacy, we are reinforcing the idea that people only have two choices while simultaneously pitting careers against each other. I strongly recommend adopting more neutral phrasing such as “career options,” “career pathways,” “diverse careers,” “many possibilities” and so on.

- Intentions of doctoral training: While I certainly do not have space in this article to delve into the broader intentions of doctoral training from a philosophical standpoint—that’s a dissertation in and of itself—I do encourage readers to reflect on and start disentangling others’ ideas for what you should be doing post-Ph.D. and center yourself in this process. It’s important also to recognize the inherent bias of our environments. When surrounded by individuals doing a particular kind of work a particular kind of way, that option can feel like the expected course. You are undergoing advanced research, study and training in a specific disciplinary area that prepares you for a variety of careers. Becoming a faculty member may be a great option—and it is also one of many.

There are so many complex factors to the decision-making process around careers, and each individual person has their own unique set of values and priorities. Something that you value is not more or less important than what someone else values. Their choices are theirs, and yours are yours. What is key here is to do the work to articulate what those values are and then apply that insight to intentionally evaluate career options. In addition, it is completely normal that your values will change over time as you gain more knowledge, perspective and experience.

Take my career as one example in a sea of many. Like so many others, I started my Ph.D. program intending to become a tenured faculty member at an R-1 institution. Fast-forward a few years, and I realized that while I enjoyed research, I had also learned that I didn’t want to spend most of my time writing grants and papers. Which are completely normal activities of a faculty member! In addition, through extensive volunteering, I had found that I greatly enjoyed working across multiple populations to provide support and help people navigate life. My knowledge, perspective and experience had changed. Luckily, despite navigating some very negative language and reactions from others, I found a career path that has provided a greater alignment between who I am and what I do.

By freeing ourselves of outdated, negative and inaccurate language around diverse career opportunities for Ph.D.s, we can empower individuals to make informed and genuine choices that reflect their personal values and aspirations. Whatever path they choose to pursue.

Briana Konnick is the senior director of career development at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago, where she oversees the career and professional development of graduate students and postdocs as well as employer engagement efforts. Briana is a member of the Graduate Career Consortium, an organization providing an international voice for graduate-level career and professional development leaders.

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed.